Essay: A Defense of Reading TTRPGs

An essay on how reading is part of playing ttrpgs (and why that matters)

My newest game, SPINE, came out of a series of questions that I’ve been considering lately about how we play with tabletop RPG books. These questions are the reason why I've prefaced this game's release with a series of essays and interviews. Among these questions are also the following about reading these books:

- When do we read our tabletop RPG books as part of play?

- How and when are game texts essential for play?

- Who is the tabletop RPG designer's priority: the player or the reader?

- How is reading part of our play experience?

SPINE has been my attempt make the RPG book part of play. It is also my attempt to push us into reading our game texts playfully, to disrupt an awkward, false dichotomy of reading and playing. This is the final essay in my series, and in it, I try to explain my perspective on reading as both a form of play and a part of play and how that has informed SPINE.

But first, what is SPINE?

SPINE is a solo TTRPG that looks like a book. In SPINE, you play as a researcher who has inherited this strange book from an estranged relative. You play by reading the book and following the prompts that you find in the endnotes. But you soon discover a catch. You are being absorbed by the book — getting lost in it. The only way to lessen its power is by defacing the text.

Piece together the story without losing yourself in it.

SPINE is free for a limited time.

So. What do these questions have to do with SPINE? First, some context:

TTRPGs as Text

SPINE evolved out of a long conversation about the textual nature of tabletop RPGs that may have started as early as the 1990s, when criticism was leveled at tabletop RPG books that were seemingly intended to be read rather than played. The critique was mostly about a lack of quality control from publishers around supplementary materials and the business models that encouraged it. It implied that these materials should be intended for play and that publishers neglected playability for a readerly audience.

This context likely informs an ENworld post by James Jacobs of Paizo in 2010, in which he justifies the intention to make supplementary materials that are not only fun to play but also fun to read, suggesting that this quality was the key to Paizo’s success:

Paizo more or less exists as a game company today (and not merely as an online RPG store) because adventures sell. If they're done right. And by “right,” I mean “fun to read.” Because I suspect that the majority of adventures published by game companies are never actually played by most of those who read the adventures.

Jacobs focuses on adventures, but he points to a shift in the perception of tabletop RPGs as more than simple instructional manuals to facilitate play. It’s important that games are fun to play, but it’s especially important that they are fun to read.

This conversation may inform Jenna Moran's Wisher, Theurgist, Fatalist (WTF, 2009) as well, which was released one year prior. Writing about WTF, she recently said,

Sometimes people suggest that I write my games more for people to read than to play, which is a little silly, because reading is what you do with text. I don't have the publishing resources to add a bunch of buttons and things to spin and mechanisms to slide the text around, much less wheels to roll around the book with and have it race other games. (Tumblr 2025)

The discussion escalated in 2019, evidenced by Rutskarn's “Boot Hill and the Fear of Dice” and Sidney Icarus's “Textual Rebellion and the Rejection of RPGs.” In "Boot Hill," Rutskarn proposed a different way of reading tabletop RPGs, a way that doesn't prioritize the author's intent and accept the text at face value. And in "Textual Rebellion," Icarus suggests approaching RPGs as "literary art in and of themselves," emphasizing that “historically, the text of tabletop RPGs has been viewed as more of a manual than a text.”

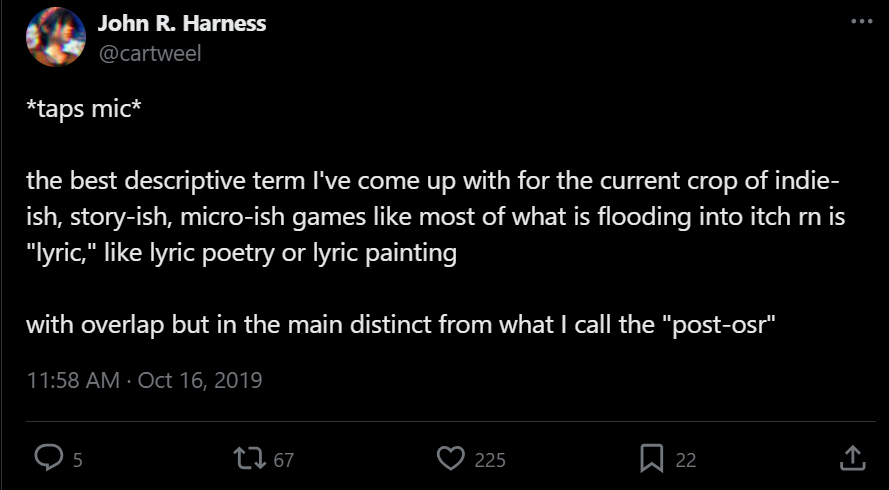

These essays influenced the emergence of the lyric game movement in the same year:

Lyric games applied these questions around interpretation to story games, producing a movement that was more concerned with artistic, poetic, and lyrical qualities than playability. It’s a big moment that treated reading as a part of play, if not its own form of play.

Since then, Jay Dragon has been brandishing this torch in her quest for a more “holistic quality” of game in Wanderhome (2021) and Yazeba’s Bed & Breakfast (2024). In 2022 she wrote “Systems of Relation,” an essay in which she explores how fiction in tabletop RPGs operates as a system analogous to mechanics, a shared imaginary world that shapes our play. She has expanded this holistic quality to include the book as a medium, exploring how these books can function as a physical prop within gameplay in Yazeba’s and now in Seven Part Pact. She has also proposed friction between players and the text as one of the critical qualities of expressionist games in her 2025 manifesto.

It's fair to say that designers’ awareness of the textual medium of tabletop RPGs has grown since 2019, and more designers recognize the need to approach the text critically, that fiction informs play, and that the physical or digital book is more than just a vessel. The frustration with tabletop RPGs that were more for reading than playing in the 1990s and an insistence upon uncritically reading RPGs as instructional manuals are amusing in the shadow of recent games like You Will Die in This Place and Triangle Agency. And last year, Chase Carter wrote an article in Rascal titled "How do you read a tabletop RPG book, and other very important questions" that suggested learning the rules is a form of play.

Even so, I feel that the popular view on reading is that it is a less critical form of engagement than playing, or that reading is not part of play — that reading and playing are a dichotomy of engagement with the game text.

In spite of the context I've cited above, I think we underestimate the importance of how we read the text of tabletop RPGs.

Reading is a form of play. Reading is also a part of play. It is not strictly relegated to learning the rules, leveling characters between sessions, or assessing a game's quality at the store. Reading occurs during play when a Game Master runs an adventure or a player relates the rules or an ability to the fictional moment. That’s especially the case for solo RPGs, in which the text is very present during play in that it facilitates the game.

SPINE is my attempt to push us into reading playfully. It’s also my attempt to understand another sort of game that disrupts this awkward dichotomy of reading and playing, which I call a text-first tabletop RPG.

Text-first TTRPGs

As I’ve said, designers have come to consciously approach the tabletop RPG as a text, as a piece of literary art, and some games have started to challenge our understanding of play as well, games like Jenna Moran’s WTF (2009), Hugh Dingwall’s and Vishãla Jecik’s Normality (2009), and most recently Liz Little’s You Will Die In This Place (YWDITP, 2025).

These games are of a category that “uses its claim to be a TTRPG to do other things as a text,” as Dingwall said when comparing Normality and YWDITP. All three of these games defamiliarize what we think of as play in tabletop RPGs by prioritizing the text and the fiction over their execution and gameplay.

YWDITP is similar to Normality in that it uses its claim to be a TTRPG to do other things as a text, which are not directly related to the experience of either running or playing the game.

— Hugh Dingwall (@objectivereality.bsky.social) 2025-07-07T04:44:37.677Z

The question of playability is always asked with these games, although YWDITP is certainly meant to be played in the traditional sense. It’s often phrased as a question: “Is this game playable?” I prefer to rephrase that question to include the implied dichotomy: “Is this game meant to be played or read?”

I propose that text-first RPGs force us to consider reading as a form of play.

Reading as Play in Tabletop RPGs.

Reading can be a form of play in any game. Reader-response theorist Wolfgang Iser says that all texts suggest “sets of instructions” or a “repertoire” that the reader assembles. They guide the reader in questioning, negating, or revising their expectation or attitude toward the text; they guide the reader as they fill in the “gaps” “to supply what is meant from what is not said.” This ideation, the act of sensemaking, is playful to me, and elsewhere Iser refers to the text and its boundaries as a “field of play” or “playground” for the reader, where they can be active and creative.

Iser also writes on how texts have scripted roles for the reader, which the reader can take or leave. You can find a good example of this in detective fiction, especially Golden Age detective fiction, wherein the reader is meant to take on a role similar to the detective, trying to solve the murder before the end of the book. Detective fiction operates as a game with its own “rules,” which gives the reader a fair chance to solve the mystery in time. Just ask S.S. Van Dine:

The detective story is a game. ... And the author must play fair with the reader. ... For the writing of detective stories there are very definite laws—unwritten, perhaps, but none the less binding: and every respectable and self-respecting concocter of literary mysteries lives up to them. (“Twenty Rules for Detective Fiction,” 1928)

Tabletop RPGs have scripted roles too. Typically, they’re written for players, who are reading to play their part within the game's fiction, or game masters, who are reading to assemble this fiction-simulating machine and to familiarize themselves with the buttons and levers necessary for operating it. Reading can be very playful within these roles.

As a game master, I have sat with rulebooks and thought, "I will tinker with these rules to fit my table." I have "edited" adventure modules as part of the interpretive labor that goes into prep. I have mulled over texts whose rules are allusive or make statements about other games, like Chris Bissette's A Dragon Game.

As a player, I have wondered at the reliability of lore and at rules that never see play yet impact the game. I have sat with provocative prompts and with character abilities that could have consequences for my character or unique potential in combat.

As players, we sometimes like to treat rules as "mathematical formulas and computer algorithms," which Stenros and Montola call "formal language" in The Rule Book, but our rules can never be so exact. And we play games not according to these written rules but rather our interpretation of them, and that is our playground.

Some games invite you to play with the spirit of the text or to read into its ambiguity. The recent Loom SRD invites players to read "laterally," declaring that the text is "interpretable as literal and as metaphorical." When the playbook says I can always hurt someone unintentionally, do I define "hurt" as causing physical pain? Mental distress?

We read “simple” instructional manuals playfully too, even those that aim for precision. In fact, to play D&D is to accept a devil's bargain at many tables, an acceptance of numerous, precise rules that govern not only characters but physical laws. This bargain enables “rules lawyers" to leverage the authority of the text to their own advantage or look for loopholes based on diction and syntax.

In Sage Advice, you’ll find some players taking delight in probing the language of their manuals like its poetry or a puzzle. And some players spit in the devil's eye by invoking the “peasant railgun,” a supposed loophole that turns the game's physical laws against its fiction.

Playing a Text-First Tabletop RPG.

But text-first tabletop RPGs are distinct from other games. These games prioritize reading as the primary form of play, shifting the scripted priority of the reader from learning and enacting the rules/fiction to playful interpretation of their meaning or significance.

The critical quality of these text-first games is that they assert that they are in fact tabletop RPGs, scripting our engagement with the text as players or game masters. In these roles, we might approach the text with the question, “how do I play?” or “how do I run this game?” And soon the text pushes us past this question, often by defamiliarizing the internal rules and conventions of tabletop RPGs. These games draw attention to the textual or verbal nature of tabletop RPGs, the chasm between author and reader, the interpretive bridge between text and play:

The author has a strong sense of what you're supposed to be doing when you play WTF.

That said — you can't read her mind.

It’s protected by the fundamental isolation of personhood and the unbridgeable divide between soul and soul!

So don’t worry too much about the author. If you can figure out what your group thinks you’re supposed to be doing, does it really matter if the author would approve? (WTF, 53)

An Arrant Thief?

According to my own definition, I am not sure if SPINE qualifies as a text-first RPG. And yet, I wanted to create a game that insists on taking the text seriously in a way similar to those cited above. I set out to make a tabletop RPG that foregrounds the textual nature of the genre, that codifies reading as play, and whose text insists upon itself in a very material way.

In SPINE, I set out to make a tabletop RPG that insists on language as the backbone of TTRPGs.

Whereas the other text-first RPGs are for multiple players, I selected the solo genre of tabletop RPGs in which reading is an especially important part of play, and I tried to push my insistence on reading as both a form of play and a part of traditional play even further. I also pushed it to be more embodied. In SPINE, reading is playing, and you quite literally become a researcher who reads and annotates the physical book in front of you.

I turned to Nabokov’s Pale Fire as a model. A classic in ergodic literature, Pale Fire insists that you play with sound and meaning constantly. It even includes word puzzles and ciphers, for example a secret message from a ghost (which I believe has yet to be solved?) and an especially witty fill-in-the-blank (“You have h _ _ _ _ _ _ _ s,” implying “halitosis” but which a character misinterprets as a poor speller’s attempt at “hallucinations”).

When you play SPINE, I hope that the text insists upon playing with words and hunting for word puzzles, although the game’s unspoken rules may signal you not to.

Endnotes are a mechanic in Pale Fire. They interrupt linear reading and interpose new information that is meant to inform (or disrupt) your interpretation. Even if you try to read the poem and the endnotes separately, you will eventually cross-reference them. In SPINE, endnotes function similarly. They are also where prompts come in, asking you to interpret the text as part of play, assess an interpretation that has been presented to you, or “remember” details about the strange relative who gifted you this book.

But I am no arrant thief! There is more to SPINE than Pale Fire’s formal inspiration. And I hope that you play it (which is also to say, read it) to see what I mean.

This is the final essay in the SPINE design series. Accompanying these essays are interviews on related subjects. This essay will be followed by an interview with Liz Little on games and ergodic literature, which will be the final interview in this series.

Free for a limited time.