Essay 1: Bookplay in TTRPGs

An essay on how we play with books in ttrpgs, also SPINE the ttrpg

Bookplay in TTRPGs, or playing with books

In May 2025, the Dice Exploder podcast featured an episode about Ten Candles with Jay Dragon. In this episode, Jay distinguishes Live Action Roleplay (LARP) — in which you roleplay as characters within a fictional setting represented by a real-world environment — from tabletop RPGs. She argues that the tabletop RPG book is an important feature that distinguishes tabletop RPGs from LARP, using her games Wanderhome and Yazeba’s Bed & Breakfast as examples:

Jay: When we play Wanderhome, we have a copy of Wanderhome open amongst us, and when we LARP, we don't have a book open amongst us that is showing us images of what it can be like, like an illuminated folio depicting to us this world.

With Yazeba's. Right. Why is Yazeba's an RPG and not a LARP? Well, first off, because you need to be able to play it in an hour and to LARP something in an hour is a big challenge. And then another thing is that the bed and breakfast is contained in the book. It's not in the world we're playing and it's in the book in front of us, and we modify the book to reflect our escapades.

And in LARP it's like, yes, you can have a space here in that you're continuously modifying to reflect your escapades, but here we've put that into the book with the rules and so it has a different relationship with us. And both of those things — you couldn't really do Yazeba's as a LARP because it would still require a copy of Yazeba's. Or you could play Yazeba's where we LARP a chapter instead of sitting at a table, but at the end of the day, we'd come back to the book, and we have a relationship with the book that's different than the relationship rules have to LARP.

This part of the episode has been echoing in my brain since it came out. It has encouraged me to think about the nature of books in tabletop RPGs and their relationship to the game’s fiction. Elsewhere in this interview, Jay describes how the RPG book “becomes a prop that is almost in its own sense LARP-like.” I like the term “prop,” but I felt as though she also begins to describe other ways for playing with books in RPGs — what I’ll call bookplay in this essay.

I want to explore those other types of bookplay and create a vocabulary that helps me talk about them with other people.

What follows are the three ways that I see the book as an object of play within tabletop RPGs:

- A Prop — An object that we play with in the real world as part of the fiction

- An Anchor — A reference object through which we can ground our play, either with setting or rules.

- An Artwork — An object whose meanings we create and re-create through play

But first… Why am I thinking about this?

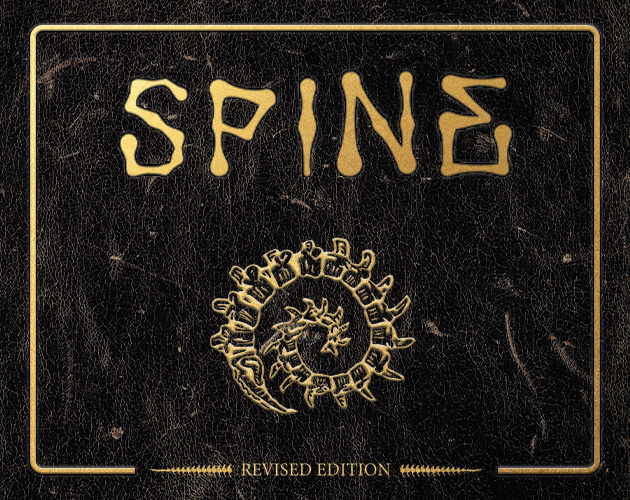

In all transparency, I'm thinking about this topic because I have written a solo tabletop RPG called SPINE, in which you play a researcher who has inherited a peculiar book from an estranged relative. You play by reading and by marking up the text to piece together the book's mysterious backstory. But the book is also slowly possessing you, and the only way to resist possession is by defacing the book.

SPINE is free for a limited time.

I’m using this essay to help me think through the design of this game. Frankly, it’s also a form of self-promotion, so please check it out.

Books as Prop.

A book can function as a prop — an object that we play with in the real world as part of the fiction

When I think of the word prop, I think of theatre in which the prop is an object that actors interact with to make the drama more real or to convey information. Jay invokes its meaning from LARP to explain how books work in her Seven Part Pact:

My wizard game Seven Part Pact, which I continuously hint at, is a game where the books are full of lore, and looking up the lore in the moment is an important part of play because that's what it is to be a wizard, it’s to be flipping through a book looking for lore.

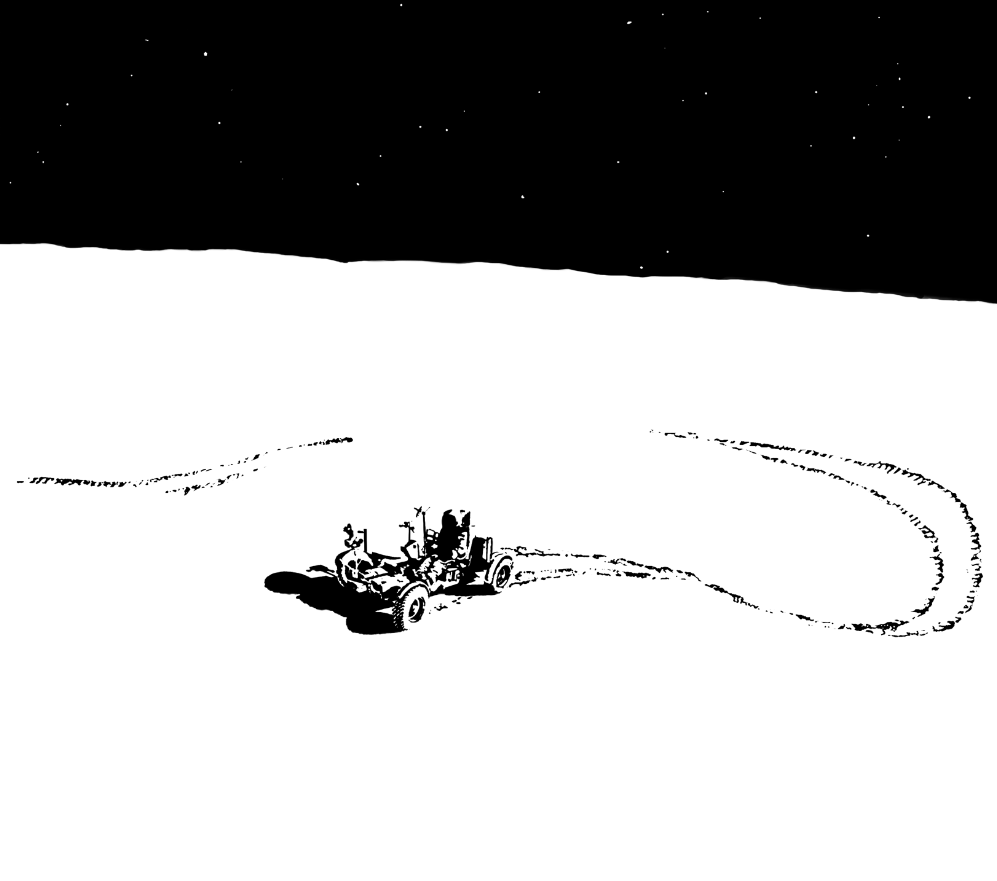

In this example, the book is an object both inside and outside of the fiction. It is a prop used by the player as they roleplay. It helps play be more “immersive” or embodied. A fun example of this is Apollo 47 by Tim Hutchings, which is a tabletop RPG about astronauts completing monotonous tasks on the moon and includes 1,177 pages of NASA reproductions as both inspiration and prop for mission control characters. You can purchase the print version on DriveThruRPG.

Please Note: This is the PDF. The print version is only available via DriveThruRPG.

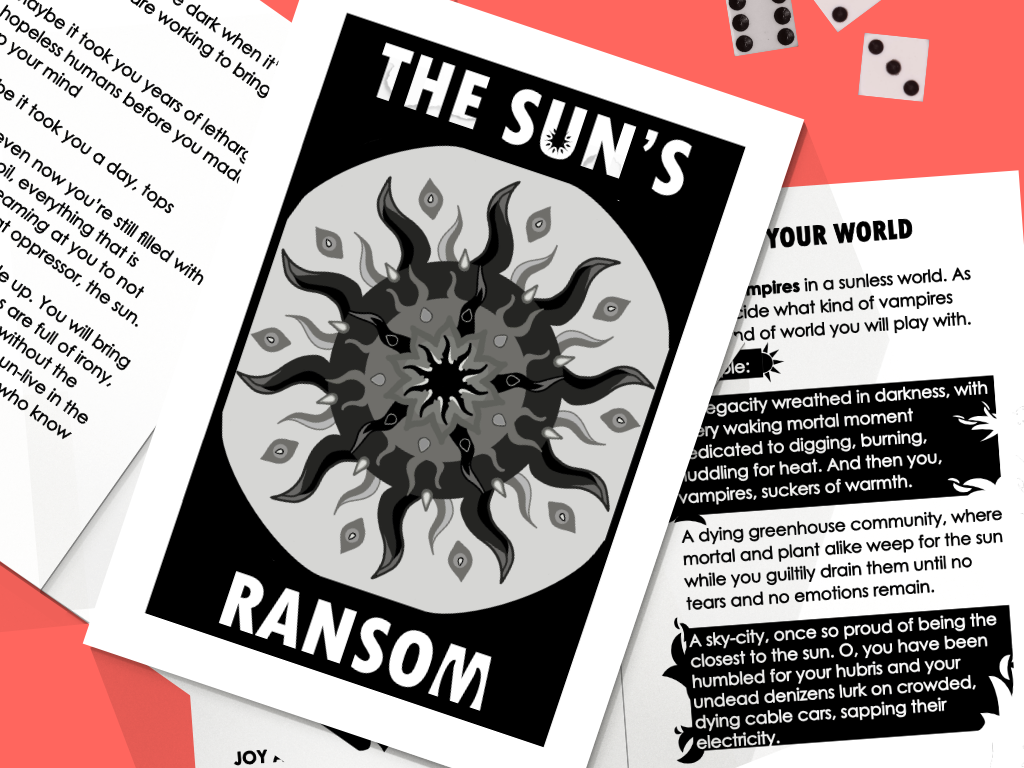

I don’t think I need to expand on props anymore than Jay does in the episode, except to say that props don’t need to be a one-for-one representation of the fictional object. Books can be props in any RPG. Your book doesn’t have to be a book. It is also the chair you’re using as an improvised weapon in your tavern brawl. Yazeba’s is a bed and breakfast. In Sun’s Ransom, the book is the sun — represented by the sun in the book’s cover art — which you block out with your dice pool.

Book as Anchor.

A book can function as an anchor — a reference object through which we can ground our play, either with setting or rules.

I haven’t heard of anyone using “anchor” as a way to describe how a book can function in a tabletop RPG; however, I think the figurative language is apt. My definition of anchor is closest to what Jay describes in Wanderhome:

Why is Wanderhome a tabletop game and not a LARP? Well, for one reason, because we're gonna be going to many different places, and LARPs struggle to make many different places feel real, right? I want us to experience a village of goats in the mountains, and then also, you know, like an underground city beneath the desert.

And LARP can't do that. LARPs not doing that. LARP can give us the majesty of the nature in the land we play on, but it cannot then extend that further.

And then also because when we play Wanderhome, we have a copy of Wanderhome open amongst us, and when we LARP, we don't have a book open amongst us that is showing us images of what it can be like, like an illuminated folio depicting to us this world.

Books function as anchors in that roleplaying games have boundless possibilities. Sometimes we need something to ground us within the infinity of play. In tabletop RPGs, that thing is a book. But we are not “chained” to these books. We choose when and how to deploy our books as anchors, so that we don’t drift away in the limitless sea of our fiction.

But it’s not just the setting, as Jay describes with Wanderhome. Anchors also present the rules or laws of our fictional world. They can ground us in what the characters (PCs or NPCs) can reasonably do and what can reasonably occur.

Also, I want to be clear that anchors do more than ground our play. They invite play. Rules lawyers love the type of play that anchors invite. They like the boundaries and the challenges that anchors provide. Sometimes these players are a bit overzealous in deploying the anchor, but this type of play can be “good” too.

Anchors also invite play in the same way that fiction invites play. Of course, anchors can be fiction. We often think of wordplay as something that an author does. Readers play with words and their meanings too. In fact, the act of reading is to play with words. Anchors invite wordplay with both fiction and, especially, rules.

Finally, anchors can be fiction in another way as well. We can use non-RPG books as an anchor too. Maybe you use The Hobbit as an anchor when playing Under Hill, By Water. Or, as Jay Dragon pointed out in an earlier draft of this essay, you can skip the rulebook completely. You can use the Lord of the Rings series as your only anchor for play.

Book as Artwork.

A book can function as artwork — an object whose meanings we create and re-create through play

My thoughts on the book as an artwork are largely derivative of the idea of keepsakes in tabletop RPGs, a term I'm borrowing from Shing Yin Khor and Jeeyon Shim, and by keepsakes I mean the (often sentimental) products or mementos that we create as part of gameplay. But I’d like to broaden the possibilities with the term “artwork” instead. And for clarity, I do believe that these books may already be works of art. But if you draw a mustache on the Mona Lisa or if you paint, draw, and collage over the pages of a Victorian novel, you are creating a new artwork. Some games invite you to transform their books into artwork.

Artwork may be embodied in a physical object, but its identity as artwork is more than its physical existence. Van Gogh’s paintings are more than oil paint on a canvas. Its aesthetic, representational properties exist beyond the physical object, granted to that object by the artist and viewer. Likewise, some tabletop RPGs invite us to transform their books into artwork by modifying or contributing to its meaning during play — including the information that they contain, their purpose, and their value to the player.

When Jay talks about Yazeba’s Bed and Breakfast, for example, she describes how “the bed and breakfast is contained in the book… and we modify the book to reflect our escapades.” She emphasizes that the players develop a relationship with the book object through playing, saying, “your relationship with the book becomes almost love-like.” Through play, we are invited to add or find new meaning in the book, to alter the information inside to record our play, to make the book ours.

The most common way that the book becomes artwork is when the players are invited to modify the book. Thousand Year Old Vampire invites you to journal in its leaves, transforming the book into a record of your fiction-making. Dictionary of Mu invites you to fill in empty pages as you play, so that the next time you play, the setting has been altered from before. Modification also includes destruction, which is almost counter-intuitively a form of creation. In Sweet Agatha, for example, you cut up its pages to create clues, which determine the outcome of your story.

But I don’t think this type of bookplay is limited to modifying a book’s physical or visual qualities. By pressing a flower in the pages or by leaving a folded note, you may imprint the book with meaning without altering the book’s physical properties. Or you could bestow a name or title on the book, like one of Duchamp’s readymades, altering its meaning and purpose: “I dub thee Kindling.”

Conclusion.

Tabletop RPGs have been engaging in bookplay all along, although I admit that I didn’t notice them until the Dice Exploder episode. But now I’m seeing it everywhere, and I am seeing how the tabletop RPG scene is beginning to experiment with bookplay in new ways. I am excited to see more of it.

I am also excited to be a part of it. My goal with SPINE is to create a game that is a book and which combines the various acts of bookplay to be as immersive as possible. And I think “immersive” is an appropriate term here.

I want the player to embody a researcher as they engage with this mysterious book, which is an anchor for rules and fiction as much as it is a prop. As the player proceeds through the book, I want them flipping back and forth from the main text to the end notes, like a scholar reading a monograph, and I want them modifying the book, writing annotations in the margins. I want them to deface the book, ripping out pages, altering the text, and more.

When they’re done playing, I want them to take the book and put it in a Little Library or the shelf of a public library for someone else to discover. And that person will have their own unique experience with the game as a result of their modification. And so forth.

Finally, I don’t like to end my posts like this — which is to say, with the illusion that my thinking on this topic is finished. I’ll change my mind on these things within the week or try a new term on for size. So, here are some questions that I am pondering after writing this essay. I invite your answers:

- I talk about books at length, but I never really define what a book is. What is a book, really? When is a game not a book?

- Are there other categories of bookplay not described here? Or useful terms that allow us to explore new possibilities?

- What examples can you think of that don’t fit these categories of bookplay?

This essay will be followed by two more. One considers the terms that we use when we as designers or players talk about our games as well as what a book’s form has to do with the bookplay therein. The other considers how reading is a form of play in tabletop RPGs.

Accompanying these essays is a small series of interviews related to these subjects, and some of these questions are answered in them. This essay will be followed by an interview with Jay Dragon on playing with books.

I look forward to ensuring that someone much smarter than I am will have the last word.

SPINE is free for a limited time.