Interview: Clayton Notestine on Book Design

An interview with Clayton Notestine about book design and how it can invite play

This interview is one of several following a series of essays on how we play with books in ttrpg, leading up to a game that I’ve been working on called SPINE, a Pale Fire-inspired ttrpg in which the book is the game and vice versa.

SPINE is free for a limited time.

I've been interviewing game designers about how games use books as props, anchors, and artifacts of play. But now I'd like to think about it not only from the perspective of game design but also from graphic design and book design. I can't think of anyone better to discuss this with than Clayton Notestine.

Clayton, from my perspective you've become a highly-regarded and well-respected peer in the ttrpg space not only for your Explorer template but especially for your thoughtful critique, theory, and tips related to layout on Explorer's Design. I personally look forward to your newsletters whenever they come out.

Although most of what I’ve written on bookplay is more abstract, I try to ground my more abstract ideas by ending with a discussion of books as a material object, considering their medium and design. Medium has the most obvious impact on how we play with books. We “flip” through physical books and we “scroll” through digital books. Beyond medium, the design of the book encourages and discourages bookplay.

Are tabletop RPGs games or are they books?

[Asa] Now, we could dive right into this discussion, but I’d rather start off with a trick question. Are ttrpgs games or are they books? And what do these terms mean to you as a designer of all sorts?

[Clayton] Ah! No designer can escape this thought experiment.

It's funny, I always avoid answering this question, not because I don't like it, but because I think it relies too heavily on assumptions. I only care about taxonomy and language as long as it serves my purposes. The moment theory starts to separate me from plain language, I try to reel myself back in.

Tabletop roleplaying games, for me, are games that are taught and played in all kinds of ways, with books being just one of its many vectors. We have folk games taught by word of mouth, like Mafia, games taught online through SRDs, and games played with books, dice, cards, boards, leaflets—the list goes on forever, and as time passes, the question loses its footing.

I think the more interesting question, for me at least, is what part of rpgs is the "play." I think many designers are making pretty implicit decisions (some explicit) to demarcate or blur the lines between the play and the teach, the rules, and everything else. If I walk into my local game store and ask, "Where are your roleplaying games?" They'll point to the books. The average person doesn't really distinguish between the game and the physical manifestation of said game—but if I walked into the same store and said, "Where is the roleplaying?" They'd maybe point to the nerds over by the tables.

So, simply put, I don't really think about "game" at all. It's too broad. For me, it's either "book" or "play" and sometimes I like to look at games and ask, "Is this book playing an active role in the play? Is it somehow inseparable from the play? Or is it somehow separate in its function? Neither answer is more correct than the other, but it does suggest an intention or goal of the designer behind the work.

[Asa] That's a really great answer and not only because it leads into my next question.

What are some notable examples of designs that "ground play" — of designs that direct the reader to engage with them and how they work?

[Asa] I'm clearly interested in how books function in play. In one of my posts I propose that one function of a ttrpg book is as an “anchor,” a reference object through which we can ground our play, either with setting or rules. And it’s not just the language but it's the art and the layout, too, that functionally ground our play. What are some notable examples of designs that ground play? Of designs that direct the reader to engage with them and how they work?

[Clayton] One of my favorite things to say is that all design is game design, because nearly all design informs or grounds play. Some might go even further and say art, layout, or even paper weight are a mechanic—but I prefer keeping those terms separate—what's important to take away from "all design is game design" is that art, layout, or any design really can ground play just as much as mechanics. If I put two identical games on a table, but one is bound as a letter-sized hardback and the other as a small pocket-sized zine—that alone would change the way people play with it. Not just because it changes how it's deployed at the table, but because it engineers different expectations in the user.

For example, I think a crucial part of a game like Dungeon Crawl Classics is that its art and design feels a little antiquated. The cheap paper, overloaded pages, and grungy art set expectations that perfectly reinforce the game's more notorious designs, like the introductory funnel and spell mishap tables.

On the flip side, I think games like Daggerheart and Draw Steel ground play in a much more cinematic style of play where players and GM exert a lot of authorship—almost showrunner sensibility—to play. The professional art style, glossy paper, foil cover, and classic D&D form factor all hook into the expectations and mental model of traditional play.

[Asa] Personally, I think about the 8.5x11 hardbacks from 3rd edition D&D, whose large format and realistic cover art resemble old tomes. They anchor play in the fantasy, pseudo medieval setting and serve as a prop in some ways too. And their resemblance to tomes, grimoires, and spell books tell us to treat them as reference objects.

[Clayton] You opened a floodgate by mentioning 3rd edition D&D in front of me. I loved the art direction of that particular edition, I think it nailed something intrinsic about D&D that none of the other editions have revisited—and that's D&D's obsession with taxonomy, its presentation of the world in an almost encyclopedic fashion.

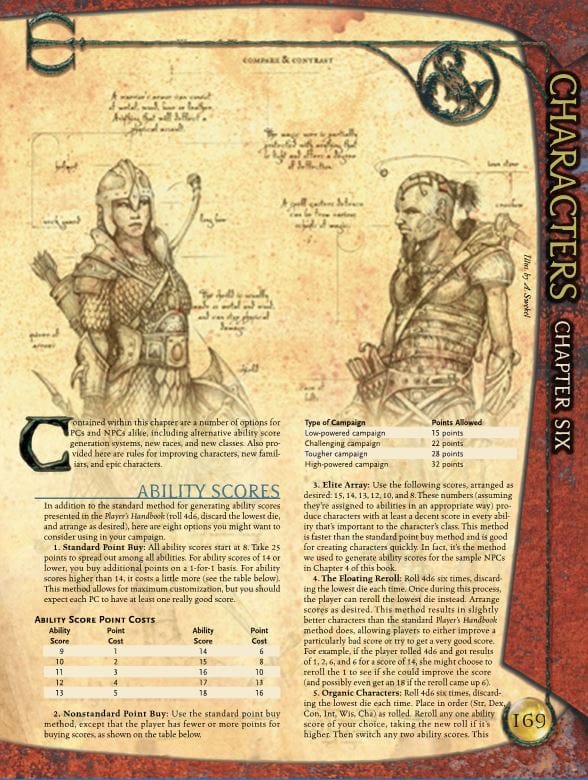

Gary Gygax was an actuary who wrote and described D&D like National Geographic or the back of a baseball card. I think 3rd edition was the first to really lean into that by making the books resemble an almost naturalist-like record. They took a lot of inspiration from Leonardo DiVinci, Galileo, and Darwin when they made those books—people who were obsessed with documenting the taxonomy and mechanics of their world. I think pairing that visual design with D&D's crunchiest edition, the edition that really started to pull apart and "explain" certain parts of the universe, was kind of brilliant.

Encyclopedic Tomes of D&D 3rd Edition

Can you say a little more about how book formats engineer different expectations and use?

[Asa] You raised a distinction between how a book is deployed in play versus how it grounds play or reinforces a setting. Can you say a little more about how a letter-sized hardback and a pocket-sized zine engineer different expectations and use? Or maybe a wire bound booklet?

[Clayton] Thinking back on deployment in play, I think moving away from letter-sized hardbacks was one of the first natural steps towards more "usable" books at the table. Not only were those books just large, and therefore an inefficient use of table space, they're almost too large to glance at. Smaller form factors are more portable and have something large formats don't—smaller subdivisions of information. You can make more compact spreads with smaller form factors.

Wire-bound books haven't quite gotten the widespread adoption they deserve. Some of them are still straddling the line between wire-bound workbooks and tomes by being too well made. You almost need the paper to be cheaper and for half of the pages to be fillable forms for people to really lean into that format's strengths.

[Asa] That would be very cool. I'd love a ttrpg that is basically an activity book or workbook, and I think one of the great strengths of those wire-bound books is how they can lay flat, which is great for writing in the book or for those solo games where you need the prompt open in front of you. That leads me to my next question.

How would you design a keepsake RPG in a way that encourages players to mark up and engage with the book?

[Asa] One incredibly cool genre of tabletop rpg that plays with the book is the keepsake genre, and in this genre the book itself can be turned into artwork of sorts. But that poses unique challenges for the designer. You put together this beautiful book and now you want people to write in it or even deface it! If you’re the designer for a keepsake game, how do you approach the book’s design in a way that encourages players to mark it up and engage?

[Clayton] If I were making a keepsake game, I'd do everything I could to make the unplayed artifact feel incomplete and unprecious to the user. A lot of keepsake and journaling games on the market today make the mistake of making beautiful books that can only be made worse by being used—it has to be the opposite.

There are some really good journaling books and products outside of rpgs that have navigated this conundrum really well. They usually have beautiful covers, a smart but unassuming interior (think: bullet journals), and directions that are either very simple on the inside, or live outside the product as videos and online instructions.

At the very least, I would be mindful of costs and production values. There's probably a cost/quality sweet spot where users can feel empowered to make mistakes without feeling like they're wasting their money. Maybe there's a way to make mistakes desirable—like the way scrapbooking gets more texture when you pull out the tape and whiteout to "fix" things.

Oh, and it probably goes without saying, but if I'm going to make a journaling game—I'm going to make sure it's with paper that can be written on. High-gloss paper is never seeing ink from a pen, no matter what the rules say.

How do ttrpg books emulate other genres or objects, like instructional manuals? And how do those design decisions influence how players engage with the text?

[Asa] Your answer brings me to a question that I wanted to ask you earlier when you mentioned how books are deployed in play. We associate different types of book designs with specific uses.

When we see something that resembles a journal or notebook, the design invites journaling. When we see a scrapbook or activity book, that book design invites those activities. Most commonly among ttrpg books, I see imitations of manuals and handbooks, for example Salvage Union or Apollo 47, which communicates that you'll use it to learn the game and for future reference. And finally, there are also really fun designs, like Yazeba’s which mimics a bed and breakfast, from the sign on the door to the shelves for trinkets.

How do ttrpg books emulate other genres or objects, like instructional manuals? And how do those design decisions influence how players engage with the text?

[Clayton] Design is partly evocation. Nothing is ever 100% new, so the elements we borrow from other genres or objects—intentionally or not—inform the audience what to expect, how to use them, and how to feel about them. Roleplaying games are often described as instruction manuals, but I'm always more interested in finding out what kind of instruction manual. Specificity is everything. Roleplaying game books can resemble countless things, but I want specificity and intentionality front and center.

As an example, TORQ, a game all about post-apocalyptic rally cars, physically resembles a real-life car manual. Same width, length, and thickness, but that's where the emulation ends. The borrowed elements give it style, tone, and portability without the real-life inspiration's maddeningly bad layout and writing. For me, that's just the right amount of emulation without losing the plot—it's still a roleplaying game. Borrow what works. Leave what doesn't.

One of these days I'm going to write an article about what cookbooks can learn from roleplaying books, instead of the other way around. Contrary to popular belief, I don't think most games can benefit from a cookbook's design. I think we're all just desperate for modular grids, white space, and decently sized margins. Everything else a cookbook has to offer is probably useless to most games.

[Asa] So what you're saying is that cookbooks could use more random tables and perhaps a section on "What is cooking"?

[Clayton] I think cookbooks could have more "play" examples and cook advice in the back.

I'd like to trade "What is an rpg?" to them broadcloth. Most roleplaying games approach that question with the intention of somehow defining or establishing the medium for outsiders. Meanwhile, in cookbooks, it might actually be good to define what "cooking" is in a book about Italian cuisine or New Orleans food, because the answers would probably be different.

"What is roleplaying?" Flattens the idea. "What is cooking?" Expands it.

[Asa] I appreciate that you found a way to redeem my awful joke by turning into something insightful, haha.

When it comes to book design, what can ttrpgs take or what have they already taken from ergodic literature?

[Asa] My final question here is about ergodic literature, which is to say books like House of Leaves, and cybertext that make the reader work as part of the reading experience and often supply many possible experiences of the text. And I've seen an effort to discuss the relationship between this type of literature and tabletop rpgs, which I think is due to our growing awareness of the fact that ttrpgs are likewise a primarily "multimodal bookish medium," at least in the way that they are facilitated.

Liz Little’s You Will Die In This Place is a ttrpg heavily-inspired by House of Leaves. Design isn’t just about teaching the game and making everything clear. There are labyrinthine designs and designs that are meant to frustrate or pose disorienting dilemmas.

When it comes to book design, what can ttrpgs take or what have they already taken from ergodic literature?

[Clayton] I might actually be succinct with this one. If someone is going to borrow or take inspiration from ergodic literature, I want them to make ergodic roleplaying games. The experience should create meaning from deconstructing roleplaying games, just like ergodic literature creates meaning from deconstructing literature.

[Asa] I'm tempted to foil your attempt to be succinct, but I think I've already borrowed enough of your time.

[Clayton] Go ahead, ask a follow up, I dare you.

[Asa] Haha, well, you asked for it! Here's my half-baked follow-up:

There are a few tabletop rpgs that defamiliarize roleplaying games in interesting ways, Wisher, Theurgist, Fatalist and Normality as two other than You Will Die In This Place. I think one of the questions they bring to the table is, "What is play?" and beyond that, "Is reading a part of play in a tabletop RPG?"

I'm curious what your thoughts are on that question, as a designer. I also want to know, Is it ever worthwhile to design or create layout in ways that challenge or require effort from the player, in ways similar to how ergodic literature challenges readers?

[Clayton] This kind of brings us back to the start of the interview. "What is play?" The game is one thing. The play is another. Ultimately, play is not in the book, it's in the player. I think reading can be a part of play in tabletop roleplaying games, just like anything else.

Designers should be allowed to challenge, experiment, and explore how they influence play. In many ways, mechanics provide friction or walls to bounce off of, why should type, color, and layout be any different? Sometimes design isn't meant to be easy, invisible, or even friendly. Not all design is fit for everyone, just like not all art is fit for hotels. If layout stops you in your tracks, it could be bad design, or it could be art.

[Asa] Well, that's a lovely way to end. It's almost like we planned it! Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts, Clayton. I appreciate the opportunity to chat with you about book design and playing with books in ttrpgs. I look forward to many more newsletters from Explorer’s Design and to enjoying just as many games in the Explorer Template!

If you want to hear more of Clayton's design thoughts, give him a follow on Bluesky or sign up for the Explorer's Design newsletter.

SPINE is free for a limited time.