Essay: How do we talk about TTRPG Books?

An essay on how we talk about ttrpg books, plus how book design invites bookplay.

On terminology and bookplay

In my last essay, I explored different types of bookplay, in which the book can function as a prop, anchor, and/or artwork.

In this essay, I’m going to look at bookplay from an abstract perspective, which is the terminology that we use to talk about tabletop RPG books and what it says about the book's intended function. I discuss three terms in particular: one common, one uncommon, and one that's deceptively simple. It wasn't my original goal with this piece, but I end by encouraging designers to be intentional or creative with the terms that they use.

But first… Why am I thinking about this?

As I say in my first essay, I was inspired by Jay Dragon’s words in the Dice Exploder episode on Ten Candles. In this episode, she says that books are one of the things that distinguish tabletop RPGs from LARP. It encouraged me to think about the nature of books in RPGs and their relationship to the game’s fiction.

I'm also thinking about this topic because I am writing a solo RPG called SPINE, in which you play a researcher who has inherited a peculiar book from an estranged relative. You play by reading and by marking up the text to piece together the book's mysterious backstory. But the book is also slowly possessing you, and the only way to resist possession is by defacing the book.

I wrote this essay to help me think through the design of this game, which is currently free and is available for download on itch.io as of today (10/14).

SPINE is free for a limited time and now available for download.

Common Terms for TTRPG Books.

In English — and this essay is limited to English terminology — we have many common terms that we use to describe tabletop RPG books: guidebooks, manuals, modules, playbooks, handbooks, splatbooks, supplements. The terms we use vary according to the types of tabletop RPGs that we’re talking about and how we use the book. For example, the term “module” suggests that it provides standardized parts that a player — specifically the game master — will interpret, "edit," and assemble for a final product of their own making.

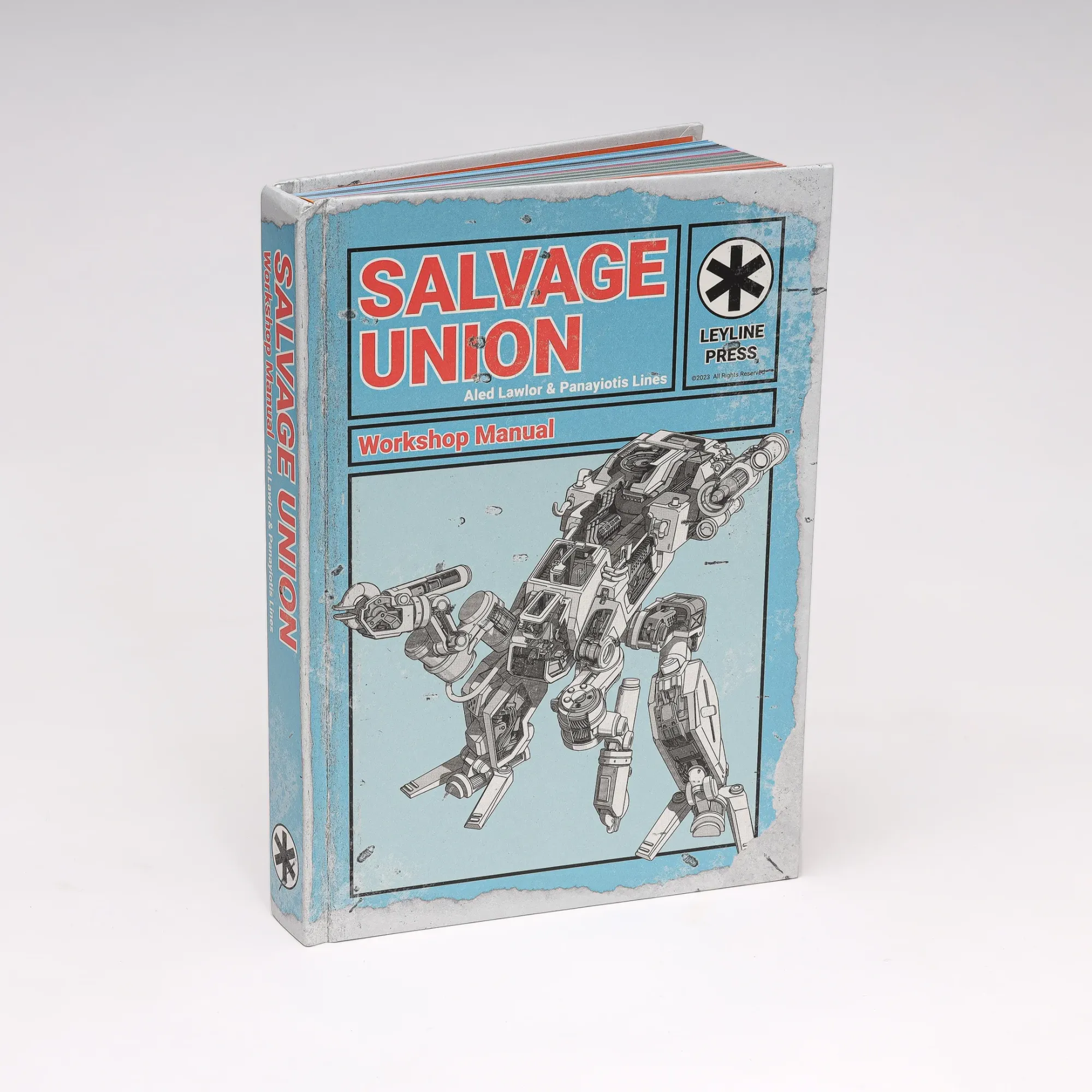

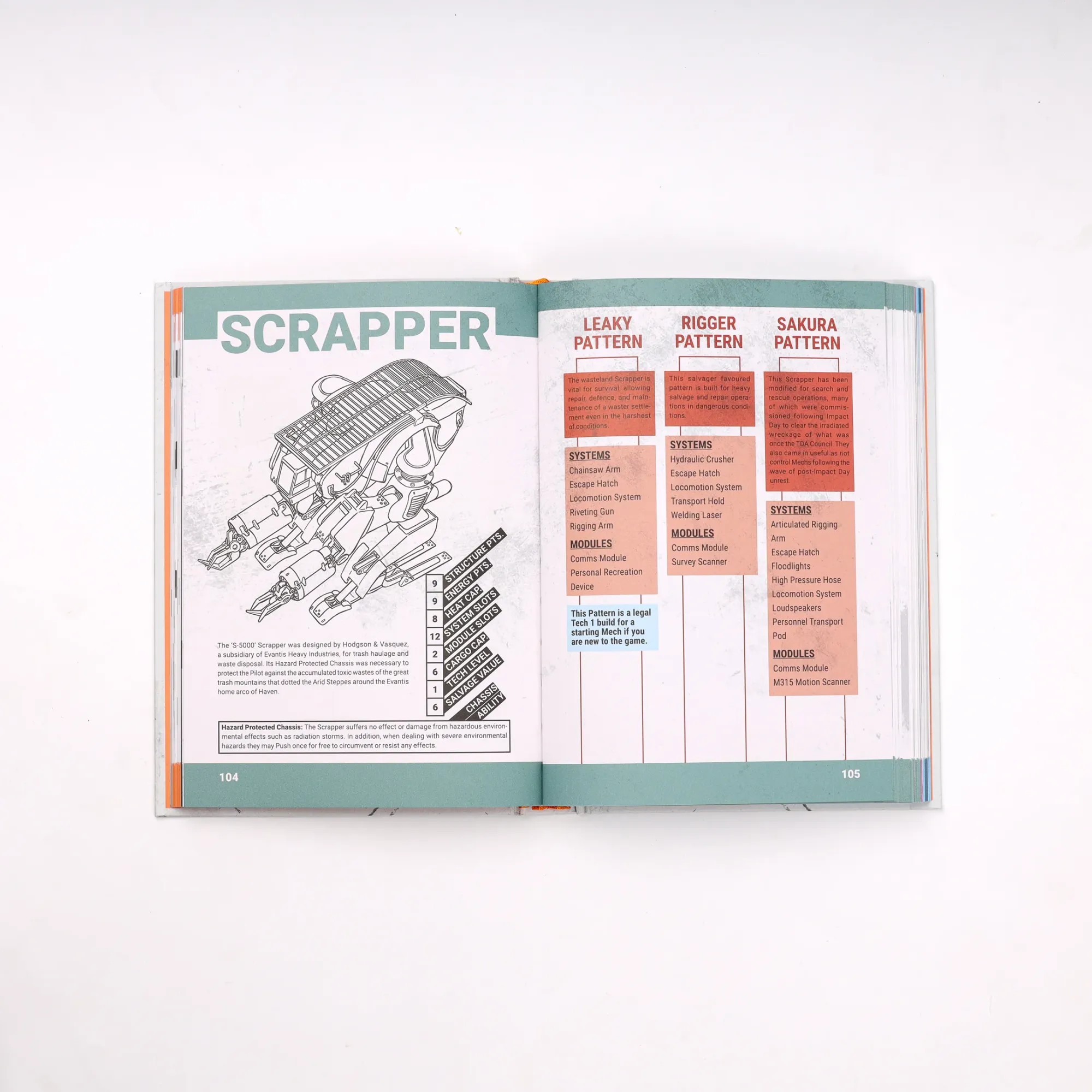

These terms also suggest how we may play with the book. Most of the common terms imply that the book will be used as an anchor or reference object, like a "rulebook" or setting "guide." Some of these terms can suggest the potential for props. The game's genre and the book's design often reinforce this. For example, your Salvage Union "manual" can be a prop for your mech's operating manual during roleplay:

Salvage Union's "workshop manual" and a technical diagram for the "scrapper." Credit: Leyline Press.

Rulebooks, Gamebooks, and Book-books

I have already listed seven common terms for tabletop RPG books, but there are three terms that I am most interested in for what they say about bookplay.

This first is rulebook. As the name implies, these books tend to outline the rules, how to play, options for playing, stat blocks, etc. Games with rulebooks lean on books as anchors, a reference object through which we can ground our play.

If I can generalize broadly here: These books are referenced on occasion but not always featured at the table. Oddly enough, although "rulebook" sounds very authoritative, many rulebooks have less authority in their books, vesting that authority in a Game Master instead. Some rulebooks invite you to disregard the book’s authority! This rule could even be the most fundamental rule of them all, a rule zero.

Rulebook may be the most common term used for ttrpg books, but it has its limits.

For example, Yazeba's Bed & Breakfast seems to avoid the term rulebook (and any term, really) in its product description. Instead, it simply says "book." Four times. When the game text does describe itself as something other than a book, it uses the term “bed & breakfast.” In fact, Yazeba’s is listed as “a downloadable bed & breakfast” on itch.io, which is just delightful. This term says a lot about the book, particularly that Yazeba’s book functions a prop — a metaphorical bed & breakfast, complete with shelves for you to put your mementos on.

Jay has described Yazeba's as "House of Leave if it were nicies."

I think "rulebook" has a hard time describing the more innovative things that some genres of tabletop RPGs are doing with their books. For example, I personally don't like to refer to a solo RPG book as a "rulebook," because it does more than hold the rules. The book facilitates play in the way that a Game Master might. In fact, you may be interested to hear that solo RPG books are separate from rulebooks in DriveThruRPG's filter. They fall under "Solo, GM-less, & Gamebooks Titles" under the Supplements & Expansions category rather than "Core Rulebook" category.

That leads me to my second term: Gamebook.

You rarely hear this term in tabletop RPGs. Sometimes, I think I hear it in conversation, but maybe they actually said "game book," which is to say "a book for a game." Often, gamebook is used to describe Choose Your Own Adventure-style games or interactive fiction. When I see it used in tabletop RPGs, albeit infrequently, it usually refers to solo RPGs.

These are books that have a large role in facilitating play. They invite play within or in relation to the book object, its prompts, its oracles.

The term seems to have bled into solo RPGs from the branching-fiction or choose-your-path style of games. Consider games like Colostle or Brambletrek, whose designers have advertised their product as "solo RPG adventure gamebook[s]."

At other times, a designer may use the term to stake a claim for their game. An upcoming campaign for Archmage's Gate identifies itself as a "solo RPG adventure gamebook," claiming to blend "classic gamebook storytelling with the freedom of tabletop RPGs" and offering compatibility with OSR systems.

To me, calling a tabletop RPG a "gamebook" can be very powerful. Yes, it invokes the genre of branching-adventure solo games, but what I love about it is that it asserts that the book is the game or that it is essential to the game, at least. I would like to see this term or one with a similar meaning used more often.

I also see people call their tabletop RPG a “book,” instead of a game. "Book" is the third term that I’d like to explore. It is deceptively simple.

When and why do we call our games books? Maybe it’s because we think of the book as the primary object and the game as something secondary contained within, which readers assemble and activate. If so, that matters.

Is it intended more to be read than played? Is it played by reading? These are questions raised about tabletop RPGs like You Will Die In This Place, Normality, and Wisher, Theurgist, Fatalist that use their "claim to be a TTRPG to do other things as a text." Or maybe we use the term because the object’s contents are more “fiction” than “game.”

Of course, we must also call them books for logistical or legal purposes (harmonization codes, taxes, etc.).

Alternatively, we may call something a book because we don’t feel the need to distinguish between the book and the game. Of course the game is a book.

In my mind, all three of these terms can imply different relationships with play:

- Rulebooks suggest play that happens outside of the book and can hypothetically occur without the book.

- Gamebooks suggest play that erupts from and within the book.

- Book games can suggest that the book and/or its fiction are central to the game's experience, that reading is an important part of play.

I recognize that I am being far too general here, but as I said, my goal was to look at bookplay from an abstract point of view.

Conclusion.

To conclude this discussion of terminology, I want to express appreciation for the innovative terms that designers use to describe their books.

On The Way to Chrysopoeia, which is an epistolary keepsake game, refers to its physical version as a travel journal, which clearly signals that it is a keepsake game.

A clever example is the almanac in the epistolary game Almanac of the Sanguine Paths by Rori Montford — which contains the oracle for your werewolf's story. (And my goodness, Rori makes the most beautiful books.) I've seen "almanac" used for supplements, but I like what the term does with the premise of this solo/duet game.

Speaking of beautiful books, check out this sparkbook: I Don't Belong Here by Adam STATION. This isn't your average "guidebook." Its visual, textual, and musical content will spark the fiction that anchors your play.

I challenge people to think about the terms they use to describe their tabletop RPG books. Does rulebook actually convey what you want it to? What would it mean for your book to be an activity book or a storybook?

What will I call SPINE’s book? It is not a rulebook. Although I like the term gamebook, I want to distinguish SPINE from interactive fiction and CYOA-style games. Sometimes the terms we use can be dangerous or misleading.

I’m going to call it a “book” to highlight its use as a prop. This term also raises questions about its complex relationship to fiction, which I'd like to encourage.

As with my last essay, I'd like to leave you with some more questions that I am pondering after writing this post:

- Are there tabletop RPGs that we wouldn't call a book? One-sheet games? Games that are passed down orally?

- Can we call digital formats books?

- Do other categories of tabletop RPGs have distinct orientations around the tabletop RPG book? Rules-lite games? Lyric games?

- What other terms can we use for tabletop RPG books and what do they imply?

- I love big books. Why do people love big books? Do they make me feel like a wizard? Do we tend to use certain book terms for games that have big books? Rulebooks? If yes, why do we invest so little authority in such big and expensive books?

Keep your eye out for my next post, which is an interview with Clayton Notestine on book design and how its medium "engineers" its use or play. It provides a more concrete analysis to complement this abstract one.

Looking Ahead: Book Form and Bookplay

The consequences of the terms that we use can be abstract, whereas the book’s form — its medium and design — can have much more concrete or tangible consequences. Medium has the most obvious impact on how we play with books. We “flip” through physical books and we “scroll” through digital books. We can’t throw a digital book across the room, but we can “divine” the location of a spell within our digital spellbook by pressing CTRL + F.

In SPINE, there is a prompt that encourages readers to push their pencil through a page. I don’t recommend doing that with a digital copy.

Beyond medium, the design of the book encourages and discourages bookplay. Design can include various modes of communication (linguistic, visual, aural, spatial, gestural) and how you apply different design concepts (emphasis, contrast, color, organization, alignment, proximity) to them. It’s not just text and illustration but also paratext, document dimensions, and material (paper weight, coated, uncoated; hardcover, softcover, etc.).

If you combine these things to make your book resemble an instruction manual, you could be signaling its use as a prop but you’re most definitely communicating the book’s use as an anchor. Likewise, you might combine these elements to look more like an activity book with connect-the-dot outlines, fill-in-the-blank fields, line art illustrations, and uncoated paper that yell, “make art with me!”

But design is important for other reasons, especially for books as keepsakes or artwork. Jeeyon Shim has said,

"This is one of the reasons why activity book publishers print on newsprint, even though better paper would take the drawing/writing materials better. The texture and obvious cheapness of the paper (and corresponding affordability of the product) signals, 'You don’t have to be precious about me.' For me the challenge is how do I make a book that invites that kind of unprecious interaction between the reader/player and the book, while making the experience of reading/play feel more precious because they’re marking the book up."

A designer may produce an obviously cheap book to decrease this cost. Alternatively, a designer may produce a more precious or purposeful interaction to outweigh the cost. There are solo rpgs (and rulebooks — and educational textbooks!) that invite people to journal, take notes, and write their answers in them. But when you can just as reasonably write in a notebook or not deface the book, it's hard to justify that act with the cost, unless there is a payoff or a good reason for it.

As I think about book forms, here are the questions that I've generated for Clayton:

- Are tabletop RPGs games or are they books?

- What are some notable examples of designs that "ground play" — of designs that direct the reader to engage with them and how they work?

- How would you design a keepsake RPG in a way that encourages players to mark up and engage with the book?

- How do ttrpg books emulate other genres or objects, like instructional manuals? And how do those design decisions influence how players engage with the text?

SPINE is free for a limited time.